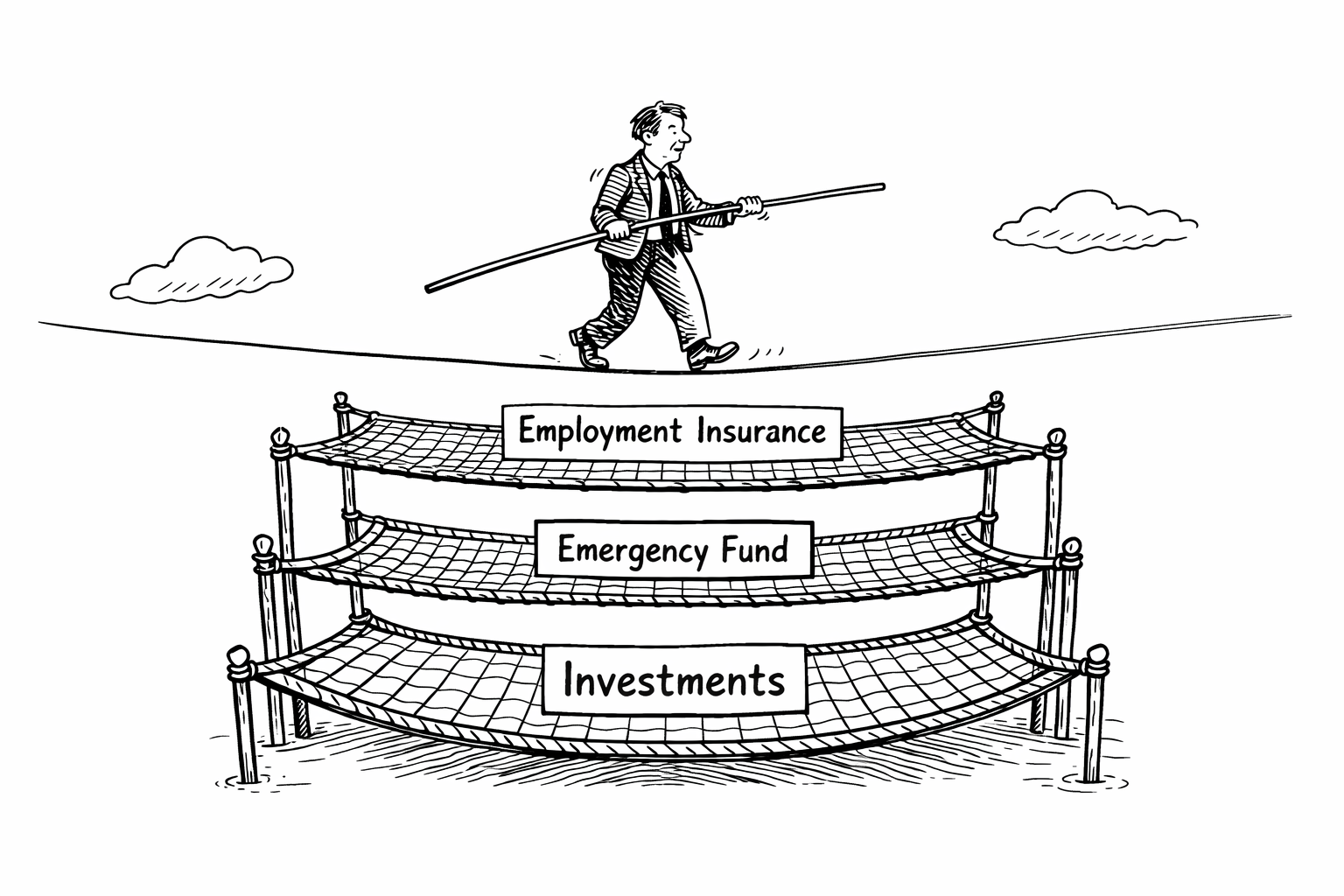

When people talk about a financial safety net, they usually mean an emergency fund. But if you zoom out a bit, there are actually three layers to a proper safety net. And one thing quietly ties all three together: your saving rate.

First layer: Employment Insurance (EI)

Before you say “duh”, pause for a second and ask yourself: do you actually know how long your EI would last?

Different countries have different EI policies. As of this writing, Canadians can receive up to 55% of their earnings, capped at $695 per week, for a maximum of 45 weeks.

For simplicity, let’s assume you spend 50% of your take-home income, meaning your saving rate is also 50%.

If the saving rate sounds absurdly high, bear with me — I’ll talk about alternatives later. But there’s something surprisingly elegant about this number.

Single-income households

Assume EI replaces about 50% of your income for six months.

Right away, you can see that EI can cover your expenses for six months. In reality, it often lasts longer because when you’re unemployed, you stop paying pension contributions and insurance, and your effective tax rate usually drops. That means your take-home pay is slightly higher than a straight 50% comparison would suggest.

When employed (50% expenses, 50% savings):

💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵

💸 💸 💸 💸 💸 🏦 🏦 🏦 🏦 🏦

When unemployed (income cut in half but still enough to cover bills):

💵 💵 💵 💵 💵

💸 💸 💸 💸 💸

Dual-income households

Now assume both partners earn roughly the same income.

When employed (same 50/50 split):

💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵

💸 💸 💸 💸 💸 💸 💸 💸 💸 💸 🏦 🏦 🏦 🏦 🏦 🏦 🏦 🏦 🏦 🏦

If one person loses their job, household income drops by 50%. That means your expense rate jumps to 75%, and your saving rate drops to 25%.

Unemployed (one income):

💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵 💵

💸 💸 💸 💸 💸 💸 💸 💸 💸 💸 🏦 🏦 🏦 🏦 🏦

In this case, not only can your income still support your lifestyle, you’re still saving 25% of your income. That’s a huge buffer.

“But my expense rate is way higher than 50%”

That’s fair — not everyone can hit that number.

First, think about how flexible your expenses actually are. A mortgage doesn’t leave much room to maneuver, but things like dining out, travel, or subscriptions are much easier to cut temporarily.

Either way, do the math. Figure out how long EI alone can carry you. If it’s not enough, that’s when you move to the second layer.

Second layer: Emergency fund

Once EI can no longer cover your expenses, you’ll need to dip into your emergency fund.

How big should it be? Opinions vary. Some people say 3–6 months. Others recommend 12 months or more.

I could say “it depends on your risk tolerance” (which is true, but also a cliché). In reality, it often comes down to personal experience. If you graduated during a booming job market, you might assume finding a new job is quick. If you graduated in the past couple of years, that confidence may be… less solid.

How long does it take to build one?

This is where the saving rate comes back in.

Your saving rate is simply the inverse of your expense rate. If you save 50% of your income, then each month of saving buys you one month of runway.

So if you want a six-month emergency fund, it takes six months to build.

Saving rate and safety net size sit on opposite ends of a seesaw. The higher your saving rate, the smaller your required safety net, and the faster you can build it.

One practical tip: you don’t need to fully fund a 12-month emergency fund before investing. You can save up a minimum buffer — say, three months — and then split your savings: half goes toward investing, half toward expanding your emergency fund.

Third layer: Your portfolio

In a true worst-case scenario — when you’ve burned through EI and your emergency fund — your final safety net is your portfolio.

This is why starting to invest early matters. Not just because “time in the market beats timing the market,” but because the longer you’ve been invested, the less likely you’ll be forced to sell assets at a bad time.

Personally, I’m a big believer in low-cost index funds. If your portfolio is something like 80% equities and 20% fixed income, it can make sense to gradually increase the fixed-income portion once you start applying for EI. Your portfolio should adapt to your risk situation, not stay static.

Conclude

I spent a disproportionate amount of time talking about EI — not because emergency funds and portfolios aren’t important (they absolutely are), but because I wanted to quantify how much your saving rate actually determines the size of your safety net.

People often think of saving rate only in the context of FIRE. What gets overlooked is how a higher saving rate buys you something even more valuable: peace of mind.

If this post helps someone see that more clearly, then it’s done its job.